Morris Brown, a primary care physician, listens to Sarah McCutcheon’s heartbeat in the exam room at his medical office in Kingstree, South Carolina, which sits in a region that suffers from health care provider shortages and high rates of chronic diseases.

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

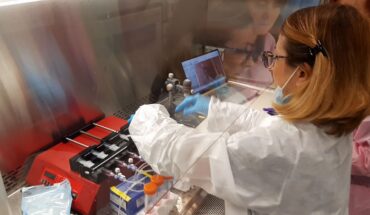

KINGSTREE, S.C. — One morning in late April, a small brick health clinic along the Thurgood Marshall Highway bustled with patients.

There was Joshua McCray, 69, a public bus driver who, four years after catching COVID-19, still is too weak to drive.

Louvenia McKinney, 77, arrived complaining about shortness of breath.

Ponzella McClary brought her 83-year-old mother-in-law, Lula, who has memory issues and had recently taken a fall.

Morris Brown, the family practice physician who owns the clinic, rotated through Black patients nearly every 20 minutes. Some struggled to walk. Others pulled oxygen tanks. And most carried three pill bottles or more for various chronic ailments.

But Brown called them “lucky,” with enough health insurance or money to see a doctor. The clinic serves patients along the infamous “Corridor of Shame,” a rural stretch of South Carolina with some of the worst health outcomes in the nation.

“There is a lot of hopelessness here,” Brown said. “I was trained to keep people healthy, but like 80% of the people don’t come see the doctor, because they can’t afford it. They’re just dying off.”

About 50 miles from the sandy beaches and golf courses along the coastline of this racially divided state, Morris’ independent practice serves the predominantly Black town of roughly 3,200 people. The area has stark health care provider shortages and high rates of chronic disease, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

Such racial inequities are especially severe across the Southeast, home to most of the country’s Black population.

But South Carolina remains one of the few states where lawmakers refuse to expand Medicaid, despite research that shows it would provide medical insurance to hundreds of thousands of people and create thousands of health care jobs across the state.

The decision means there will be more preventable deaths in the 17 poverty-stricken counties along Interstate 95 that comprise the Corridor of Shame, Brown said.

“There is a disconnect between policymakers and real people,” he said. The African Americans who make up most of the town’s population “are not the people in power.”

The U.S. health care system, “by its very design, delivers different outcomes for different populations,” said a June report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Those racial and ethnic inequities “also contribute to millions of premature deaths, resulting in loss of years of life and economic productivity.”

Over a recent two-decade span, mounting research shows, the United States has made almost no progress in eliminating racial disparities in key health indicators, even as political and public health leaders vowed to do so.

And that’s not an accident, according to academic researchers, doctors, politicians, community leaders, and dozens of other people KFF Health News interviewed.

Federal, state, and local governments, they said, have put systems in place that maintain the status quo and leave the well-being of Black people at the mercy of powerful business and political interests.

Joshua McCray, of Kingstree, South Carolina, retired as a public bus driver after he caught COVID and nearly died. During the pandemic, Black Americans were more likely to hold jobs — in fields such as transportation, health care, law enforcement, and food preparation — that the government deemed essential to the functioning of society, making them more susceptible to the virus.

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

Legacy of racism

Across the nation, authorities have permitted nearly 80% of all municipal solid waste incinerators — linked to lung cancer, high blood pressure, higher risk of miscarriages and stillbirths, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma — to be built in Black, Latinx, and low-income communities, according to a complaint filed with the federal government against the state of Florida.

Federal lawmakers slowed investing in public housing as people of color moved in, leaving homes with mold, vermin, and other health hazards.

And Louisiana and other states passed laws allowing the carrying of concealed firearms without a permit even though gun violence is now the No. 1 killer of kids and teens. Research shows Black youth ages 1 to 17 are 18 times more likely to suffer a gun homicide than their white counterparts.

“People are literally dying because of policy decisions in the South,” said Bakari Sellers, a Democratic former state representative in South Carolina.

KFF Health News undertook a yearlong examination of how government decisions undermine Black health — reviewing court and inspection records and government reports, and interviewing dozens of academic researchers, doctors, politicians, community leaders, grieving moms, and patients.

From the cradle to the grave, Black Americans suffer worse health outcomes than white people. They endure greater exposure to toxic industrial pollution, dangerously dilapidated housing, gun violence, and other social conditions linked to higher incidence of cancer, asthma, chronic stress, maternal and infant mortality, and myriad other health problems. They die at younger ages, and COVID shortened lives even more.

Disparities in American health care mean Black people have less access to quality medical care, researchers say. They are less likely to have health insurance and, when they seek medical attention, they report widespread incidents of discrimination by health care providers, a KFF survey shows. Even tools meant to help detect health problems may systematically fail people of color.

All signs pointed to systems rooted in the nation’s painful racist history, which even today affects all facets of American life.

“So much of what we see is the long tail of slavery and Jim Crow,” said Andrea Ducas, vice president of health policy at the Center for American Progress, a nonprofit think tank.

Put simply, said Jameta Nicole Barlow, a community health psychologist and professor at George Washington University, government actions send a clear message to Black people: “Who are you to ask for health care?”

The end of slavery gave way to laws that denied Black people in the U.S. basic rights, enforced racial segregation, and subjected them to horrific violence.

“I can take facts from 100 years ago about segregation and lynchings for a county and I can predict the poverty rate and life expectancy with extraordinary precision,” said Luke Shaefer, a professor of social justice and public policy at the University of Michigan.

Starting in the 1930s, the federal government sorted neighborhoods in 239 cities and deemed redlined areas — typically home to Black people, Jews, immigrants, and poor white people — unfit for mortgage lending. That process concentrated Black people in neighborhoods prone to discrimination.

Local governments steered power plants, oil refineries, and other industrial facilities to Black neighborhoods, even as research linked them to increased risks of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, cancer, and preterm births.

Morris Brown, a primary care physician, says that South Carolina lawmakers’ refusal to expand Medicaid will result in preventable deaths because many people who live near his medical offices in Kingstree and Lake City cannot afford to go to a doctor. (Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News)

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

An ineffective government response

The federal government did not even begin to track racial disparities in health care until the 1980s, and at that time disparities in heart disease, infant mortality, cancer, and other major categories accounted for about 60,000 excess deaths among Black people each year. Elevated rates of six diseases, including cancer, addiction, and diabetes, accounted for more than 80% of the excess mortality for Black and other minority populations, according to “The Heckler Report,” released in 1985. During the past two decades there have been 1.63 million excess deaths among Black Americans relative to white Americans. That represents a loss of more than 80 million years of life, according to a 2023 JAMA study.

Recent efforts to address health disparities have run headlong into racist policies still entrenched in health systems. The design of the U.S. health care system and structural barriers have led to persistent health inequities that cost more than a million lives and billions of dollars, according to the National Academies report.

“When COVID was first hitting, it was just sort of immediately clear who was going to suffer the most,” Ducas said, “not just because of differential access to care, but who was in a living environment that’s multigenerational or crowded, who is more likely to be in a job where they are an essential worker, who is going to be more reliant on public transportation.”

For example, in spring 2020, the North Carolina health department, led by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Mandy Cohen, failed to get COVID testing to vulnerable Black communities where people were getting sick and dying from COVID-related causes at far higher rates than white people.

And Black Americans were far more likely to hold jobs — in areas such as transportation, health care, law enforcement, and food preparation — that the government deemed essential to the economy and functioning of society, making them more susceptible to COVID, according to research.

Until Joshua McCray, the bus driver in Kingstree, S.C., got COVID in his mid-60s, he was strong enough to hold two jobs. He ended up on a feeding tube and a ventilator after he contracted COVID in 2020 while taking other essential workers from this predominantly Black area to jobs in a whiter, wealthier tourist town.

Now he cannot work and at times has difficulty walking.

“I can tell you the truth now: It was only the Good Lord that saved him,” said Brown, the rural physician who treated McCray and many patients like him.

Federal and state governments have spent billions of dollars to implement the Affordable Care Act, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and other measures to increase access to health care. Yet, experts said, many of the problems identified in “The Heckler Report” persist.

When Lakeisha Preston in Mississippi was diagnosed with walking pneumonia in 2019, she ended up with a $4,500 medical bill she couldn’t pay. Preston works at Maximus, which has a $6.6 billion contract with the federal government to help people sign up for Medicare and Affordable Care Act health plans.

She is convinced that being a Black woman made her challenges more likely.

“Think about how many centuries the same thing has been happening,” said Preston, noting how her mother worked two jobs her entire life without a vacation and suffered from health conditions including diabetes, cataracts, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Today Preston can’t afford to put her 8-year-old son on her health plan, so he’s covered by Medicaid.

In email exchanges with the Biden administration, spokespeople insisted that it is making progress in closing the racial health gap. They said officials have taken steps to address food insecurity, housing instability, pollution, and other social determinants of health that help fuel disparities.

President Joe Biden issued an executive order on his first full day in office in 2021 that said “the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and exacerbated severe and pervasive health and social inequities in America.” Later that year, the White House issued another executive order focused on improving racial equity and acknowledged that long-standing racial disparities in health care and other areas have been “at times facilitated by the federal government.”

“The Biden-Harris Administration is laser focused on addressing the health needs of Black Americans by dismantling persistent structural inequities,” said Renata Miller, a spokesperson for the administration.

The CDC, along with some state and local governments, declared racism a serious public health threat.

U.S. Rep. Alma Adams, a North Carolina Democrat, pushed for “Momnibus” legislation to reduce maternal mortality. Yet federal lawmakers left money for Black maternal health out of the historic Inflation Reduction Act in 2022.

“I come to this space as an elected official, knowing what it is like to be poor, knowing what it is like to not have insurance and having to get up at 3, 4 in the morning with my mom to take my sister to the emergency room,” Adams said.

In the 1960s in North Carolina, Adams and her family would take her sister Linda, who had sickle cell anemia, to the emergency room because they had no doctor and could not afford health insurance. Linda died at the age of 26 in 1971.

“You have to have some sensitivity for this work,” Adams said. “And a lot of folks that I’ve worked with don’t have it.”

Dr. Morris Brown’s medical practice serves the predominantly Black town of Kingstree, S.C. (population roughly 3,200). The area has stark health care provider shortages and high rates of chronic disease, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

hide caption

toggle caption

Gavin McIntyre for KFF Health News

‘Like having two strikes against you’

The website for Kingstree depicts idyllic images of small-town life, with white people sitting on a porch swing, kayaking on a river, eating ice cream, and strolling with their dogs. Two children wearing masks are the only Black people in the video, even though Black people make up 70% of the town’s population.

But life in Kingstree and surrounding communities is marked by poverty, a lack of access to health care, and other socioeconomic disadvantages that have given South Carolina poor rankings in key health indicators such as rates of death and obesity among children and teens.

Some 23% of residents in Williamsburg County, which contains Kingstree, live below the poverty line, about twice the national average, according to federal data.

There is one primary care physician for every 5,080 residents in Williamsburg County. That’s far less than in more urbanized and wealthier counties in the state such as Richland, Greenville, and Beaufort.

Edward Simmer, the state’s interim public health director, said that if “you are African American in a rural zone, it is like having two strikes against you.”

Asked if South Carolina should expand Medicaid, Simmer said the challenges South Carolina and other states confront are worsened by health care provider shortages and structural inequities too large and complicated for Medicaid expansion alone to solve.

“It is not a panacea,” he said.

But for Brown and others, the reason South Carolina remains one of the few states that have not expanded Medicaid — one step that could help narrow disparities with little cost to the state — is clear.

“Every year we look at the data, we see the health disparities and we don’t have a plan to improve,” Brown said. “It has become institutionalized. I call it institutional racism.”

A July report from George Washington University found that Medicaid expansion would provide insurance to 360,000 people and add 18,000 jobs in the health care sector in South Carolina.

“Racism is the reason we don’t have Medicaid expansion. Full stop,” said Janice Probst, a former director of the Rural and Minority Health Research Center in South Carolina. “These are not accidents. There is an idea that you can stay in power by using racism.”

South Carolina’s Republican governor, Henry McMaster, in July vetoed legislation that would have created a committee to consider Medicaid expansion, saying he did not believe it would be “fiscally responsible.”

Expanding Medicaid in the state could result in $4 billion in additional economic output from an influx of federal funds in 2026, according to the July report.

Beyond health care coverage and provider shortages, Black people “have never been given the conditions needed to thrive,” said Barlow, the George Washington University professor. “And this is because of white supremacy.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF.